Deadly Grass Strikes an Unlikely Species

If you’re from the Western U.S. and have a dog, you’ve probably heard of “fox tails.” This is a generic term referring to a number of species of spiky grasses. You wouldn’t think a piece of grass would be too hazardous, but it is not uncommon for them to be fatal in animals. The problem isn’t so much that the little spikes are sharp, but that they have lots of tiny little barbs facing away from the tip. So if the tip punctures something, the barbs make it stay put and help it “migrate” further into tissue. In veterinary medicine, this can wreak havoc on animals in a number of ways. The most common would be penetrating the nose of a curious dog or cow romping and sniffing around where these grasses grow. It is also possible for the grass spikes to puncture the skin or even be inhaled past the nose and deeper into the trachea and lungs. Regardless of where they penetrate, migration into tissues causes physical trauma and drags environmental bacteria through the animal’s tissues resulting in severe inflammation and damage. There have been cases where the grass enters through the skin on the chest and migrates all the way into the lungs, or starts in the nose and migrates into the brain!

Last month, I did my first post-mortem exam on a Pacific pocket mouse (PPM#27), which was a bit of a challenge as these little guys measure about 5cm from head to toe (smaller than my thumb). The Disease Investigations folks provide diagnostic support for many of our conservation programs at the Institute, and this case represents why that relationship is so valuable.

This particular pocket mouse was one of the founder animals in the pocket mouse conservation breeding program conducted by the Recovery Ecology group. He was brought to the breeding facility in 2013 from the San South Mateo population on Camp Pendleton.

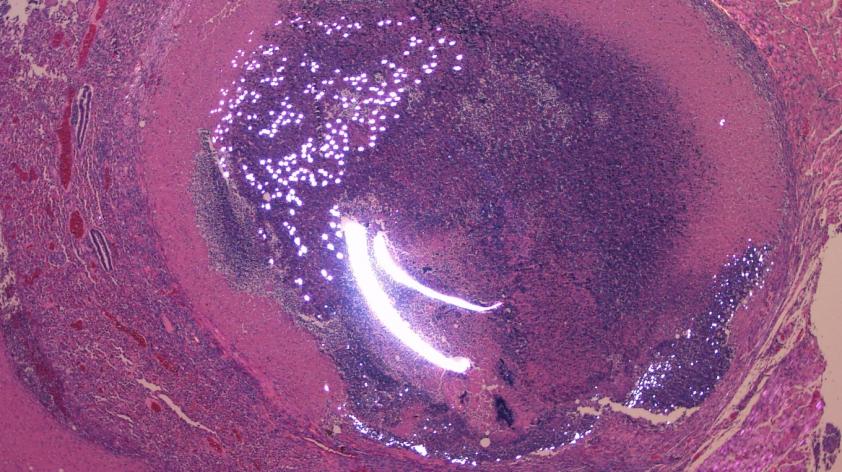

He was noted to have difficulty breathing by researchers at the breeding facility, who called the emergency on-call veterinarian at Harter Veterinary Medical Center. Supportive treatment and antibiotics were administered, but unfortunately he died shortly after. Despite the tiny size, our fantastic necropsy staff discovered an abscess in the thoracic. This explained the animal’s respiratory distress prior to death. Microscopic examination of this lesion showed several fragments of plant material embedded in the center of the abscess (See images below).

It is difficult to confirm the origin of the material in the pacific pocket mouse, but researchers responsible for the care of these mice suspect that Stipa pulchra seeds (or "purple needle grass"), is the culprit. This plant species is considered part of the normal diet of Pacific pocket mice, and is fed routinely at the breeding facility. We don't know for sure if the lesion in this pocket mouse was the result of inhalation of plant material or puncture through the esophagus after swallowing. While this is unfortunate case, he lived well beyond the expected life-span of a wild Pacific pocket mouse and was a valuable, successful breeding male in the recovery program for this endangered species. He has sired 7 offspring, four of which are still at the conservation breeding facility. The other three were released earlier this year in Laguna Coast Wilderness Park. This past August, 40 pups were trapped at the release site, the first ever confirmation that the captive born PPM are reproducing in the wild ( http://institute.sandiegozoo.org/science-blog/captive-born-released-paci...). Genetic analysis has determined that PPM #27's genes are present in these first successful wild born litters!