Aviary Patrol

Our keepers are constantly on the lookout for any abnormalities in the collections they oversee. So when a bird is sick in an aviary, they notice. Recently a couple of diamond doves (Genopelia cuneata) were brought to the veterinary hospital due to weakness and/or neurologic signs.

The next line of defense in animal health are the clinical veterinarians. Some would say they’ve seen it all given the diversity of rare and endangered species they’ve cared for over the years. This case would argue in favor of that, as they quickly suspected the cause of the doves’ clinical signs to be due to a parasitic infection and began treatment.

These diamond doves were heavily infected, and thus the treatment the clinical veterinarians implemented was not able to save them. However, post mortem exams by the Disease Investigations team were able to confirm the vet’s diagnosis by identifying the characteristic parasites in the muscle of the birds (Figure 1).

The culprit: Sarcocystis.

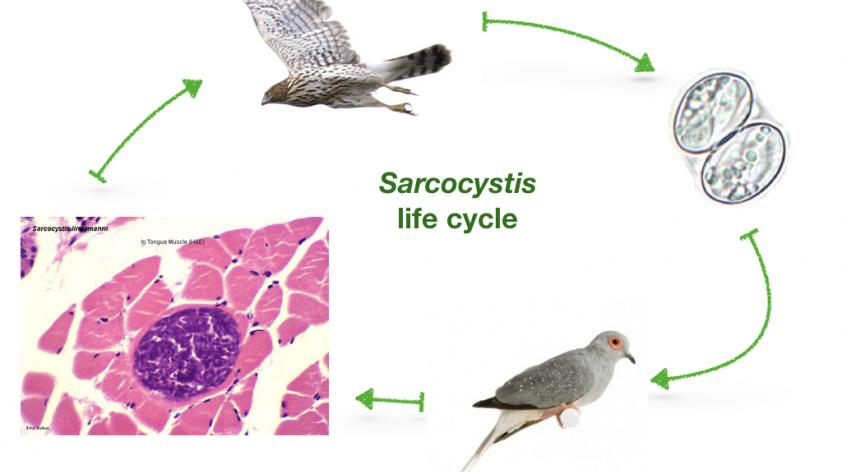

This infectious organism represents a large group of protozoal parasites that infect many animals, both wild and domestic. The life cycle is complex, but involves both a predator species and a prey species.

The parasite replicates in the intestine of the predator, and infective “oocysts” (eggs) are passed in the feces into the environment. Here, a prey species can ingest oocysts, which then spread the parasite to multiple tissues in its body. While the parasite can go anywhere, one particular tissue of interest is the skeletal muscle (“Sarco-“ comes from the Greek word meaning “flesh” and “cystis” indicates the parasite encysts itself in the flesh. Gross).

Now the prey’s flesh is loaded with the parasite, and the predator comes along, eats it, and voila! – the parasite has successfully propagated itself.

Unfortunately, when the parasite is spreading throughout the body and encysting in the tissue, the body treats it like any other infection and tries to combat it. The subsequent tissue damage can be fatal, especially when organs like the brain, lungs, and heart are involved.

It is helpful to identify the specific infection affecting the birds, so we can take additional steps for prevention.

There are several predators that can pass the parasite in their feces and contaminate an environment. We used molecular techniques to speciate the parasite and identify it as Sarcocystis calchasi. This is important in order to predict WHICH predator it likely came from. In this case, the species of parasite indicates that the predator host was a raptor (a predatory bird like a hawk, falcon or eagle – not a velociraptor for you Jurassic Park fans).

We’ve seen this parasite in the feces of both sharp-shinned hawks and Cooper’s hawks found on Zoo grounds. Opossums are notorious for harboring different types of Sarcocystis dangerous to many animals (such as S. neurona, the cause of equine protozoal encephalomyelopathy or “EPM,” which is a big deal to horse owners), but we can let them off the hook in this case.

Because we were able to rapidly identify this infection, several other birds exhibiting signs of disease were successfully treated. Go team!