Deadly parasites in the blood

As pathologists at San Diego Zoo Global, when we receive animals for necropsy we always do a thorough systematic examination in order to determine the cause of death. Depending on the species, we may focus in certain tissues based on its most common diseases. That is the case of the blood in birds, as we routinely make ‘impression smears’ or ‘cytologic preparations’ by gently pressing a sample of lung against a glass slide. Since it is a highly vascularized tissue - hence bloody - circulating blood cells are easy to see microscopically in those impressions.

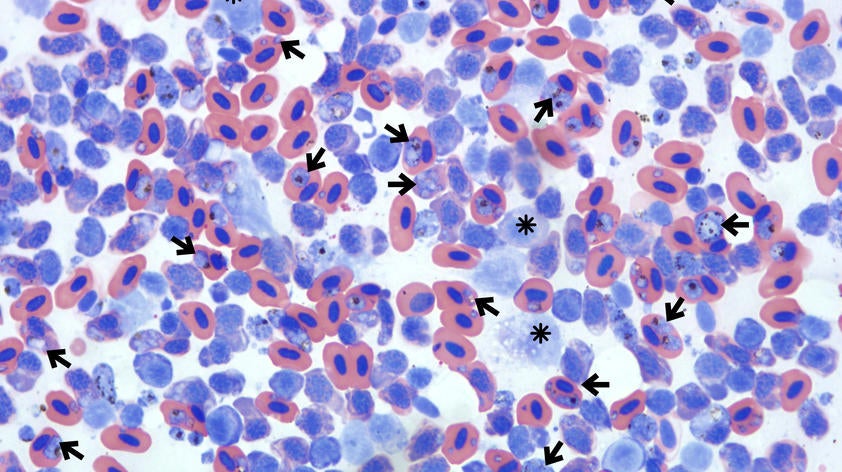

We look for blood parasites (hemoparasites) which are fairly common in many avian species. These protozoan organisms usually infect red blood cells, but white cells are affected in some cases. There are several types of hemoparasites and it is not unusual to find them in wild birds, in which the infection is considered ‘endemic’ and subclinical, meaning that a parasite is normally present in a species of a given region.

Actual disease only develops when other factors compromise the immune system. Transmission occurs through mosquitoes that act as vectors. But birds that are not normally in contact with mosquitoes at their specific habitats, will be very susceptible. Their immune system is considered ‘naïve’ against hemoparasites, and will get overwhelmed by the infection. Penguins are among those species, and mortalities are not uncommon.

Sadly, with climate change and rising temperatures in many regions, mosquitoes are proliferating, persisting through more months in the year, and/or reaching new areas, with the risk of spreading infectious agents with them.

Towards the end of 2019, Disease Investigations encountered a deeply unfortunate example of this situation. Kiwikiu or Maui parrotbills that were in the process of, or were released in a recently restored mountain region they historically inhabited in the Hawaii islands, died due to avian malaria. About that time a media release talked about the relocation of these highly endangered birds and described the decades-long multi-institutional conservation efforts to re-establish their population.

The birds were shipped overnight to us for necropsy, where lung impressions revealed a severe infection in the blood cells, and this was complemented by histopathology. Avian malaria is a disease caused by approximately 40 species of protozoa of the genus Plasmodium which causes damage and death of red blood cells, resulting in fatal anemias. The Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory confirmed Plasmodium relictum as the specific agent involved in all of the cases.

So, what happened with the kiwikiu? It looks like there were many more mosquitoes than expected that season, and maybe they even reached higher elevations in the mountains.

Whatever happened, it resulted in inevitable transmission of the disease to the recently released birds and they were unable to fight the infection. Unfortunately, this could mean that the newly restored mountainous area may be now unsuitable for kiwikiu survival and recovery…only time will tell, but we hope for the best.