Fire eagles

During the devastating wildfires currently raging around California, I have been fortunate to observe wildlife behaviors that highlight the adaptability and resilience of nature in the face of catastrophe. I have been leading an ongoing program conducting conservation research on the golden eagle populations resident to Northern Baja California, Mexico. This eagle program was formed in partnership with CONANP, the Mexican federal government wildlife agency, and the Mexican renewable energy company IEnova. SDZG has been engaged by IEnova to monitor the population dynamics and movements of golden eagles in relation to its wind energy development site near the USA/Mexico border and provide scientific data to inform the management and mitigation of any potential ecological impacts.

In addition to aerial surveys of breeding golden eagles conducted via helicopter, a sample of eagles have been captured by Mexican raptor expert Juan Vargas and carefully fitted with a lightweight, solar-powered, GPS backpack transmitter. These transmitters provide high-resolution location data from each tagged bird at time intervals of just 10 seconds – which enable me to map in 3D the bird’s flight trajectory and altitude with incredible accuracy and detail. These data are also remotely uploaded to a server each day via the cellular network, eliminating the need to recapture and disturb the bird to obtain the collected GPS fixes. I have been tracking golden eagles in Baja for several years and have observed some amazing movement behaviors, including multiple long-distance exploratory flights > 55 miles (90 km) across the border into the USA as the birds forage for prey.

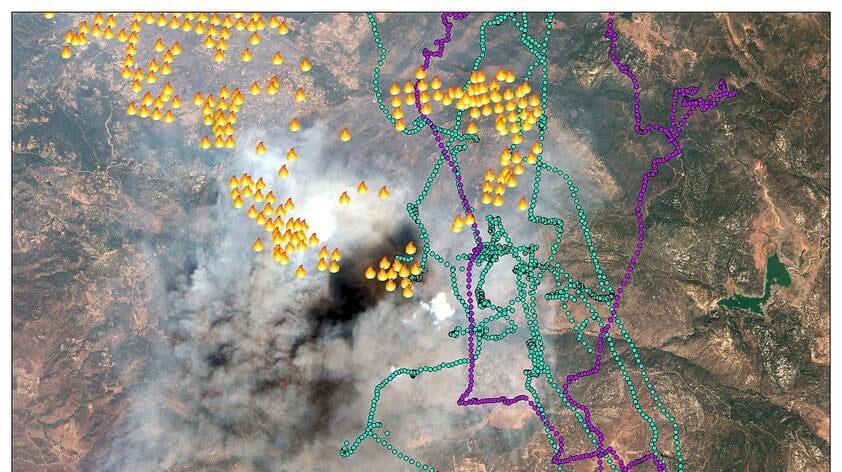

A large wildfire named the Valley Fire recently burned 17,500 acres of the Cleveland National Forest in south San Diego County near Barrett Lake and the town of Alpine before it was extinguished after three days through the heroic actions of local fire fighters. As this wildfire blazed, I tracked a pair of golden eagles comprising an adult female and her recently fledged male offspring as they made multiple flights across the border from their nest near the Baja city of Tecaté. Remarkably, both these eagles made several flights directly over the active Valley Fire site. I was able to confirm this phenomenon by plotting the movement trajectories of the eagles over digital maps of the wildfire coverage that I derived from contemporaneous ESA Sentinel-2 satellite imagery and NASA MODIS and VIIRS thermal satellite data.

These flights may have been an eagle foraging strategy as they searched for prey animals flushed into the open by the heat and flames. Golden eagles are also known to opportunistically scavenge and they may have also been on the lookout for the carcasses of burned prey animals. The female eagle has been previously tracked flying around the Barrett Lake area, so it may have been simply making typical foraging flights across its territorial range accompanied by its offspring, as opposed to being attracted to the fire and smoke. Nevertheless, this observation reveals an intriguing aspect of golden eagle behavior and shows how this species can interact with an important native habitat under increasing pressure from wildfires. Our project also demonstrates how cutting-edge technology can open previously unknown windows into the behaviors and ecology of an endangered species with a view to enhancing its conservation management.