How a chicken egg brought me full circle to a life dream

Whether it was running in the backyard with my Golden Retriever, Bailey, or trying to get a close look at butterflies when they would briefly land on a flower, animals continuously sparked my interest as a child. I needed to know more about them, and I wanted to find out what made them tick. Without a google search to rely on, this meant frequent trips to public libraries where I spent hours reading about different dog breeds, venomous snakes, and animals as big as an elephant and as a small as an ant. I was intrigued by the diversity of the living things around us and the power of a human animal bond.

My teachers, specifically Mr. Jim Spandikow, quickly noticed that I always had a science book in my hand and recommended that I join a program called BE WiSE.

BE WiSE (Better Education for Women in Science and Engineering) is a program for middle school girls that aims to educate and grow science and engineering opportunities specifically for women. I was able to enroll in a large variety of classes ranging from learning about my graphing calculator to my favorite event, an overnight visit at the San Diego Zoo Global's Institute for Conservation Research (ICR).

Riding up to ICR, my dad and I were immediately in awe of the beautiful building. Once inside, each student was given a miniature lab notebook, Institute pen, and name badge, which made us all feel like scientists.

We learned about the California Condors and their impressive wingspan, we even got to hold a feather! We listened to different animal sounds trying to decipher what animal they belonged to. We candled a chicken embryo allowing us to see the blood vessels and the little heart beating. We met with actual researchers that described their own paths to joining the field of research.

Even though at the time I understood very little of the science, it became apparent I could have a career that combined my love for animals with my love for learning.

My passion for science and continuing my education led me to the University of California, Davis, where I graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Animal Science with a Specialization in Companion Animals. Throughout my years at Davis, I worked at two veterinary hospitals and performed research on swine. I visited numerous centers including the Center for Aquatic Biology and Aquaculture, the California Raptor Center, and received hands-on experience with cattle, equine, goats, sheep, and laboratory animals.

I knew the animal world was where I belonged.

After graduating from UC Davis, I wanted to continue my education and chose to pursue a Master’s in Biology from California State University, San Marcos (CSUSM). The coordinator for the program recommended I contact the Institute for Conservation Research based on my previous experiences. I was so excited about the opportunity to work at the very research center I had visited in middle school, but was nervous about the caliber of knowledge required. After meeting with Dr. Thomas Jensen, a Senior Scientist, and Patricia Byrne, a Senior Research Associate, in the Reproductive Sciences department I knew the Institute was where I wanted to be.

Through what I describe as serendipity, Dr. Jensen’s lab is the same lab where I first observed chicken embryos during my BE WISE trip. Little did I know, chicken embryos would now be something I frequently work with.

I first visited the Institute for Conservation Research 11 years ago as a middle schooler with a love for animals, and now I am conducting my own project aimed at species preservation in one of the very labs I visited- hard to believe my luck!

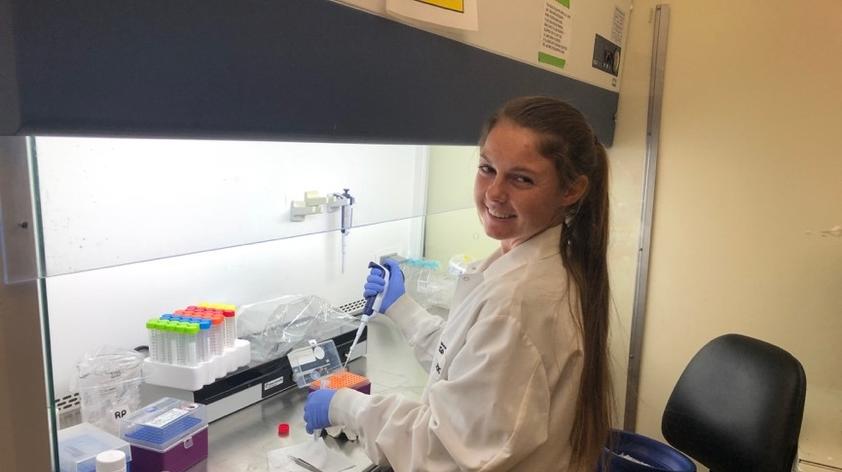

Using developing chicken embryos as a culture system, I am transplanting cryopreserved testicular tissue from the Frozen Zoo® onto a membrane within the chicken egg. As the chicken embryo grows and develops, it supports the transplanted tissue and keeps it alive. My goal is to add steroids, LH, and FSH to the tissues in hopes of creating an environment that induces spermatogenesis.

This would have a tremendous impact on conservation as the recovery of spermatogenesis from cryopreserved testicular tissue would result in sperm that can be used in artificial reproductive techniques, such as in-vitro fertilization. This means that the genetic material from a deceased individual could be brought back into the population years after it died!

I never thought I would end up performing research in the same lab I idolized as a child, but I followed my passion and it led me right back to where I started.

Kelley Kramer is Master’s student from California State University San Marcos.