Pathology stories part one: A day in the life with Dr. Steven Kubiski

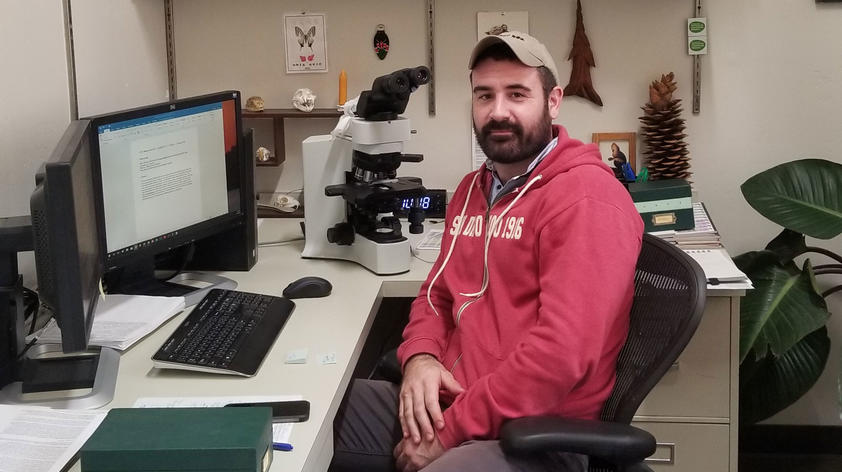

Dr. Steven “Steve” Kubiski sits at his desk, surrounded by the day’s work and his plant collection which runs the gamut from succulents to leafy tropicals. The shelves on the walls over his shoulder house driftwood, small green boxes of microscope slides, and a tortoise shell. On his desk is a display case of small skulls and a candlestick made of a vertebra. Several coffee cups are within elbow distance, waiting for their turn to be used. A green box of tissue sample slides, dropped off that morning by a colleague, sits at his elbow. The office resembles what you might imagine the modern version of a classic natural history professor’s office might look like.

But the researcher sitting behind the desk is a modern scientist, specializing in emerging viruses, and he spends his days using his expertise to end disease as a driver of extinction.

During vet school, he thought he’d be a “regular” veterinarian, with a specific interest in cardiology. He knew that wildlife inspired him, but the pieces hadn’t yet come together to lead him into the world of wildlife medicine. Then everything changed: William Karesh came and gave a talk related to his book, Appointments at the Ends of the World: Memoirs of a Wildlife Veterinarian, and the seed was planted. Steve took pathology classes his sophomore year, then histology, and suddenly everything clicked: infectious disease led him to be a pathologist.

Most recently, Steve was part of a team studying an unknown disease affecting multiple species of snakes. These snakes have had severe spinal lesions, and the cause has not yet been determined. The case is bizarre, and a working group consisting of clinical veterinarians, nutritionists, reptile managers, along with Steve and his epidemiologist colleague, Dr. Carmel Witte, was formed to try and identify a cause of the disease. It affects snakes across multiple species, and types of species, which makes it more challenging. Snake families most affected seem to be pythons, but there have also been rattlesnakes seen with symptoms.

Steve’s day starts early in the morning. He arrives at the Disease Investigations building just off of Zoo grounds by 7:00 or 7:30 AM. “You can get more done if you come in before all the meetings,” he says. And meetings will dominate most of some days, bookending a rotating list of trainings to be conducted, samples that need assaying, and time for ongoing research projects. Diagnostic cases need to be read and follow-ups scheduled.

Mid-morning, Steve heads to the Disease Investigation team’s daily meeting, where they convene to go over what happened the day before and make plans for the rest of the current day’s work. They meet in a small conference room, with a long oval table surrounded by golden-brown upholstered chairs. Hooded microscopes and books line the counters around them, and a canvas of a magnified tissue sample in varying shades of purple hangs behind them. Reports are read out loud, questions are asked, and each section of the team speaks in turn. They share slides of a recent surgery and the diagnostics produced on the animal in question. One of the team members shares good news: a positive test result for an animal showing signs of healing elicits celebration from the whole team. “He [the animal] can go home!” The animal is healing and will go back to its exhibit, healthy.

After the morning meeting is lunch, before heading into the afternoon rotation of ongoing research and assay development, the process of testing specimens to find out if any diseases are present in the samples. He’s working on a few ongoing projects at any given time, but the team is focused on a disease affecting birds at the moment, as well as a disease impacting snakes. It isn’t just the animals within the confines of the park that are part of the team’s work; local populations of species are critical to monitor for disease as well. Local species may bring diseases to the zoo population or vice versa, and it’s important to track pathogens on a population level.

One thing Steve would like to see is something of a conceptual idea: he wants to create an avenue for collaboration so that his pathology team can work with toxicologists to create a broader understanding of the diseases impacting endangered wildlife. “We diagnose all kinds of diseases, but don’t really do toxicology,” he says. “But environmental toxins are a huge worldwide threat.” In particular, he cites toxins that can cause changes to an animals genetic information and therefore be passed on to future generations. Natural disease in the wild can be very difficult to study because there’s no way to control for all factors, so this kind of research can be groundbreaking. This is exactly why Steve got into wildlife pathology.

Later in the day, Steve might go to a “show and tell” with some of the animal care staff at the Zoo or Safari Park, a bit of feedback and information sharing that connects the team with the rest of the folks working with the animals there. More research and more training punctuate time spent planning for the next day’s work. At the end of the day, the green slide boxes are closed and catalogued, the samples are stored, and the last meetings are adjourned. Steve closes his office to go home. As the lights dim in the offices and lab spaces, he’s another day closer to understanding the viruses that threaten species, and another step closer to ending extinction.

Thanks very much to Dr. Steven Kubiski for taking the time to chat with me and for sharing about his current and ongoing research. You can learn more about Dr. Kubiski’s work through his profile on the Institute for Conservation Research website.