Rhinos and Reproduction

I have been here with SDZG for almost two years now, and you would think things would settle down. But no! For nearly a year we have been conducting ultrasound exams on the reproductive tracts of the six southern white rhino females that came here from South Africa in late 2015. There was a steep learning curve for everyone and I felt like mine was straight up. We got good at it though.

Our amazing trainers worked with the rhinos to make sure they felt safe and comfortable in the chute while we worked on our ultrasonography skills at the back end. Eventually we were conducting up to two ultrasound sessions per week on some females, others once per week. It’s important to collect all the data we can about this species because we want to be as ready as humanly (and rhinoceros-ly) possible when it’s time to take the next steps, like artificial insemination and embryo transfer.

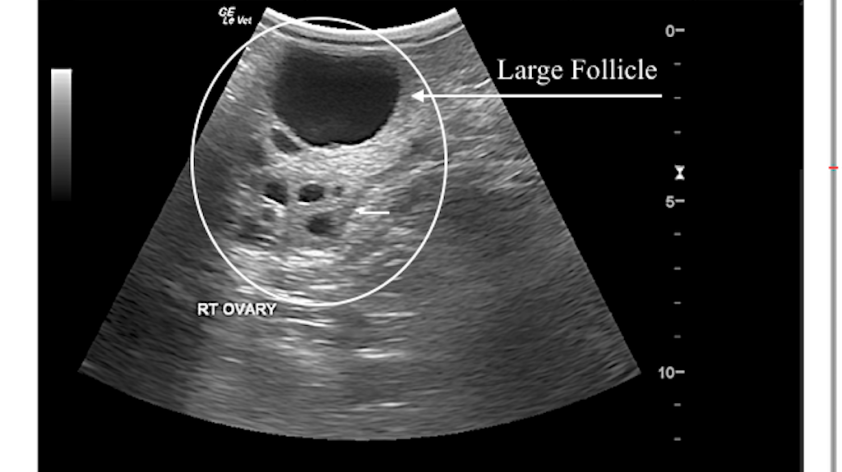

But what did we find out? Something I was not expecting, not at all. Only one female (Wallis, you may have heard of her) was ovulating. The other females would do everything right – except ovulate. Their follicles (the ovarian structures that house the egg) would grow as expected.

But around the time I thought it should ovulate (burst open and release the egg, making it available for fertilization), it would just keep growing. Eventually it would max out in size and then start regressing (shrinking) – and then another one would do the same thing on the other ovary. I loving/frustratingly call this ‘follicular purgatory’. Every female did this, except Wallis– she is a rock star.

So what to do? How do we get a female pregnant if she is not ovulating? We thought, ‘well, can we help her ovulate?’

In horses (our model species), ovulation can be induced with a hormone treatment, making it a predictable event, which makes planning when to artificially inseminate much easier and more successful. I worked with horses before I came to the zoo and used this treatment with all of the mares I studied.

There was also a research paper published that had used this treatment in rhinos, so we thought the chances were good it would work with our females. But we wanted it to be consistent, something we could rely on. We applied specific criteria for its use: the follicle must not only be growing (rather than shrinking), but must also reach a minimum diameter of 35mm before we give her the hormone treatment.

Next, we wanted to know if the hormone: 1) causes the rhino to ovulate, and 2) if so, when? To answer these questions we conducted ultrasound exams 24, 36, and 48 hours after treatment. It was a lot to ask of the rhinos, but they have been champs about it.

What did we find? That 1) yes it made them ovulate 9 out of 11 times, and 2) when a rhino does, she always ovulates between 36 and 48 hours post treatment.

One female failed to ovulate on two occasions, but rarely is anything perfect. Now we have a treatment that is not only repeatable, but predictable. And we are ready to take our next steps toward artificial insemination.

Fingers crossed we can make that a reliable procedure as well.