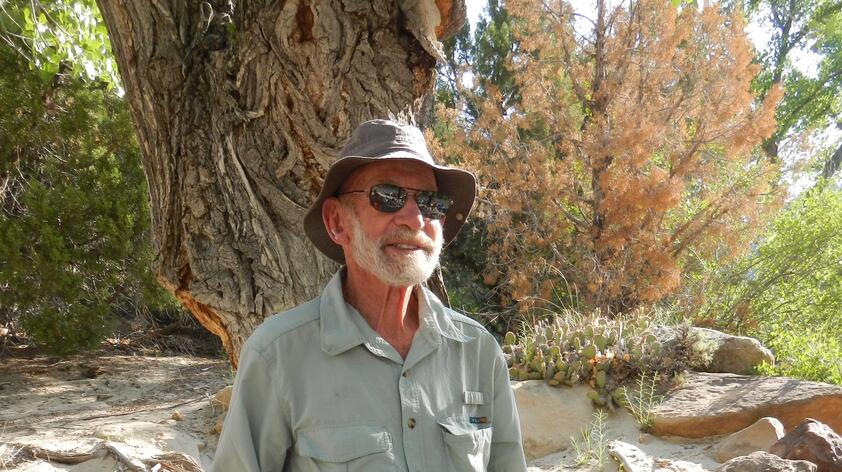

Tribute to Dr. Michael Soulé, 1936-2020

I first met Michael Soulé in 1984, as a young graduate student at the University of California, San Diego. As was usually the case with Michael, he was on a mission. And even back then, it had to do with the important concept of how natural landscapes are connected to each other.

Michael grew up in San Diego, and like most kids back then, he spent much of his free time chasing horny toads in his neighborhood canyon. Whenever I mention horned lizards to an adult who grew up in San Diego, I invariably get the same response, “what ever happened to those little guys? There used to be so many of them, and now I never see them anymore.” Well, I’m pretty sure it’s not that Michael collected them all.

But Michael did grow up inspired to understand what it is that determines why species like horned lizards don’t seem to be able to persist in fragmented landscapes. Using aerial imagery, which was relatively new technology at the time, Michael looked at the pattern of development in San Diego, and realized that it was a vast landscape of islands. He saw that we had developed virtually all of our mesa tops, where the land was flat and easy to build on, and left our steeper canyons intact, to exist as islands of natural habitat surrounded by a sea of development.

Michael set about recruiting a small army of undergraduate and graduate students to conduct surveys of the birds, mammals, plants, and invertebrates in 37 of these canyon fragments. If you lived on the edge of a canyon in Point Loma, Pacific Beach, La Jolla, Solana Beach, Encinitas, Mid-City, Golden Hill, or East San Diego then my fellow students and I probably traipsed through your yard at least once.

It’s a real testament to Michael’s enthusiasm and persuasiveness that he convinced more than a dozen of us twenty-somethings to spend our evenings not at the campus pub, but instead setting live traps for mammals at night and then getting up at the crack of dawn to mark, measure, and release the native mice and rats we captured in them. Although we lived in balmy San Diego, even all these years later I still remember how cold those canyon bottoms were at 5am.

Without going into all the details, I can say that the San Diego Canyon Study, as it came to be known, became a keystone contribution in the field of conservation biology that inspired decades of research on how the size, age, and connectedness of fragmented habitats are critical to their ability to support biodiversity into the future, not just here in San Diego, but in fragmented landscapes around the world. Here at home, the canyon study results were used as a model in the design of our MSCP, or Multiple Species Conservation Plan preserve system, of which the natural lands surrounding the Safari Park are an important part.

Never satisfied with the status quo, Michael took his ideas and understanding of the need for keeping natural habitats connected to the continental level. Together with David Foreman, he founded the Wildlands Project in 1991 and served as its Chairman of the Board. Now known as the Wildlands Network, their vision is nothing less magnificent than to create a continental-scale network of connected habitat, linking together wildlands from Mexico to the Yukon, from Florida to Newfoundland, from Baja California to the Brooks Range and the Bering Sea. In 2007, Michael was honored with San Diego Zoo Global’s Conservation Medal for Lifetime Achievement.

In the Introduction to his groundbreaking book, Conservation Biology: The Science of Scarcity and Diversity, Michael wrote, “There are probably conservation biologists who would be reluctant to lecture their students on how to love nature. In their defense, one could argue that loving nature is not a scientific subject, that ardor reveals subjectivity, and, above all, that a biologist is not an expert on loving nature. This is rubbish. No one has more expertise on loving nature than the professional naturalist or manager who has spent his or her lifetime studying and admiring plants and animals.”

Thank you, Michael, for being a conservation biologist who wasn’t afraid to encourage us to love nature in all its complexity, and to dedicate our lives to conserving wild things and wild places.

Photo above courtesy of Wildlands Network.