The Widespread Work of a Conservation Warrior

Imagine your life savings is kept outside in a fenced-in area next to your house. Now imagine a stealth, nocturnal creature, as beautiful as it is terrifying, randomly swiping chunks of it, and you have little or no recourse. For many people who keep livestock in rural Kenya, this is a common situation—their livelihood is at risk. As frustration and losses rise, people understandably want to eliminate the culprit, and is the basis of the human conflict with the African leopard Panthera pardus.

In June 2017, San Diego Zoo Global (SDZG) began working with communities to find solutions for this human-animal conflict. “It feels like the government is not doing enough, so this is a welcome project,” said Ambrose Letoluai, SDZG research assistant from northern Kenya. When I met with him at the Zoo, he was clad in classic Kenya attire and stunning beaded accessories, which garnered some attention—and selfies—from visitors. Gracious and kind, it was easy to picture Ambrose in his home country interviewing people about their interactions with and feelings about local wildlife, and leading thein-situ research team. “I love this job because it provides a solution to a problem we have had for so long: the conflict between wild animals and livestock,” he said.

After a successful hunt, the agile and powerfully built African leopard can easily carry a dead, full-grown impala up a tree for a leisurely meal. They are predominantly nocturnal, solitary animals marking their home range with aromatic urine and claw marks. This big cat is native to 35 African countries. The African leopard,one of nine leopard subspecies, can live over 20 years, and subsists opportunistically on an array of food from carrion to reptiles to large mammals, including occasional livestock. With a conservation status of Vulnerable, its most daunting threat is living in the shadow of humans: habitat loss and fragmentation, reduced prey base, retaliatory killing, and poaching all take a toll. Despite its dramatic good looks and crafty hunting acumen, the African leopard’s ecology and biology is not well understood. “We cannot conserve what we don’t understand,” said Nicholas Pilford, Ph.D., Scientist, Population Sustainability, SDZG. “Because these cats can be found in so many different places and they are so adaptable, people may not think they need conservation, but that’s not true.” Between 2008 and 2016, the overall range of leopards was reduced by 60-percent, mostly due to a lack of information and study. “Places researchers thought they were, they were no longer,” he added. SDZG is working with communities to flesh out a deeper understanding about this elusive and elegant predator.

Jumping to Solutions, Not Conclusions

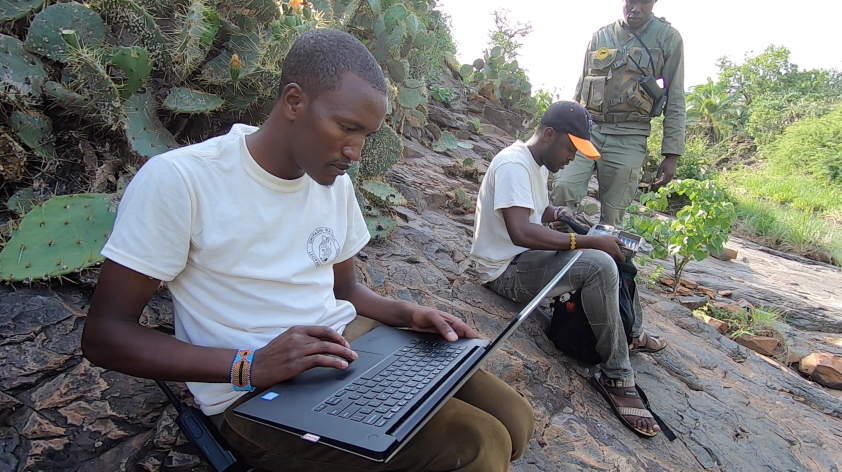

To acquire accurate data about African leopard populations (and individuals) in northern Kenya, which includes Laikipia county, the Loisaba Conservancy, and the Mpala Research Center, and covers over 260 square miles, the team set up field cameras. “It’s a cost effective way of counting the cats,” said Nick. In three trial studies, researchers used perfume-scented posts to attract the leopards so individuals could be documented. That data is being analyzed.

Meanwhile, Ambrose heard from a community member who insisted there was a black leopard in the area, so the team placed a dense grid of motion-activated field cameras nearby. It was the first time a black leopard was recognized in field camera images. A startling discovery was that out of 55 leopards documented, five of them were melanistic, appearing solid black instead of a striking golden coat with dark rosettes. Nighttime video footage shows that when the cats were close to the camera, the infrared light revealed their underlying rosettes, and as they moved away from the camera, they literally “faded to black.” Wow! (See video below.)

To better understand the where, when, and what of human-animal conflict, cameras were placed around 12 livestock bomas (corrals) to record which carnivores were visiting and when, and to see if pet dogs were an effective deterrent to hyenas. Additionally, 80 families are part of a study to see which is more effective prevention: half the households received wire to add height to their boma walls, while the other half got passive “lion lights” that blink brightly at potential predators. It’s important to listen to the feedback from each family and to balance the cost of supplies and the efficacy of each strategy to find what works and what the homeowner wants.

To further reduce conflict between leopards and livestock, the project has developed a Community Reporting Network to document when and where leopards and other large carnivores attack livestock. Nineteen people in seven communities are designated liaisons—with cell phones and solar-powered battery chargers—and ready to respond to conflicts. People are eager to solve this problem, and so far, none of the phones, chargers, or 72 field cameras have been lost. “The equipment has been taken care of very well,” noted Ambrose. Community meetings are held every three months to keep people apprised of progress and get their feedback. There’s also an annual Leopard Celebration Day, where people come from miles around to celebrate contributions to the project. “It’s a chance for people to see friends and relatives from other communities,” said Nick. “The celebrations have a fun reunion feel to them, while sharing the latest leopard updates,” said Nick.

Ambrose has also helped local women diversify their revenue stream. He explained that women come together and make beautiful handcrafted accessories with colorful beads to sell to the tourists. But that market fluctuates so he suggested they make soap to sell in the communities and package it in discarded plastic containers, which reduces waste. As their business took off, they needed a name for the collective and the women decided on Chui Mamas, meaning Leopard Mamas. “Two years ago, they didn’t like leopards much, and now they want the name!” said Ambrose. And that’s another beautiful reason why Ambrose is known as a Conservation Warrior across Kenya and beyond.

Lions are another are another potential livestock predator. Listen to that cub!